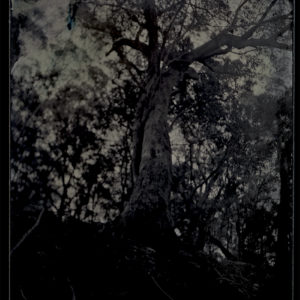

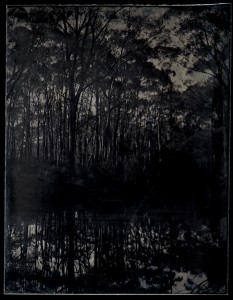

When I’m not playing alchemist, I’m an artist (who coincidentally works principally in alchemy) – you can read a bit more about my practice and see some more examples of my work on my website. Recently I got to do one of the most absurdly fun things anyone has managed to come up with yet – take wet plate photography on the road in The Blue Mountains.

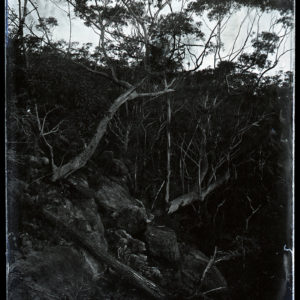

I was lucky enough to be offered a place at BigCi – Bilpin International Grounds for Creative Initiatives, an artist residency, where I had proposed to build a darkroom in the boot of my car and make glass plate negatives in the field. I got to drag a 4×5″ Speed Graphic, a bunch of glass plates, and a few bottles of collodion on the two day drive from Adelaide to Bilpin, NSW, and then spend a week frolicking.

The project was informed by the work of Harry Phillips, a photographer working in and around Katoomba from around 1909 to 1944. He photographed The Blue Mountains extensively and produced souvenir booklets for the tourist trade. These booklets are significant pieces of ephemera today, and despite being produced in remarkably large print runs, they are now somewhat rare. Harry Phillips, as well as being an incredibly dapper gentleman, was instrumental in shaping the popular interpretation of The Blue Mountains and played a part in influencing our relationship with the Australian landscape as a whole. You can read more about him in The Far-Famed Blue Mountains of Harry Phillips, by Phillip Kay (ISBN: 0909325456), and there’s a small but excellent sample of his images available right on flickr, thanks to the Blue Mountains Library. Harry Phillips worked in Dry Glass Plate rather than Wet Plate, but for the work I wanted to make wet plate was the better option. It’s good to remember that the sources that inform your art practice are sources, not guidelines.

The intention was to create wet plate collodion negatives to be printed as waxed Salt Prints either at Bilpin or when I got back to Adelaide. It turns out that getting the negative process to play nicely was enough work and I didn’t get a chance to make any prints when I was at BigCi. I hope to get them completed in the next few months now that I have the luxury of a full lab to work in. I set off from Adelaide with the following:

- A Dark Box

- Silver Bath, freshly sunned (9% Solution of Silver Nitrate)

- 400ml of Collodion (Reh’s New Generation formula)

- Developer (Lea’s Sugar Developer)

- Fixer (Ilford Rapid Fix, 1+4 Dilution)

- 20 litres of water, half a dozen eggs

- Nitrile Gloves, a respirator, goggles

- Trays of various sizes

- A 4×5″ film holder modified for glass plates, 4×5″ Speed Graphic, Tripod

- Glass, glass cutter, sharpening stone, brushes, etc

My Dark Box was of absurdly simple construction. It consisted of a bunch of particle board and MDF left over in the workshop put together as a box that I figured was about big enough to fit my upper body in . It also had a piece of red perspex left over from building the lab, and some curtain block-out fabric I found at my dad’s place. It was, basically, a big box with a red window that I could sit next to, with the fabric draped over me and a respirator mask on, and work in safelight conditions to make and process wet plates. It took some getting used to!

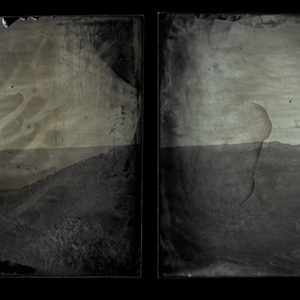

I kept this box in the boot of my car with all of my chemistry, and for each shot I wanted I would have to set up my silver bath and all of my trays inside. I’d pour a plate, wait a few moments for it to set and then sensitise it in the silver bath. Then, loading the plate in the holder, I’d scoot off to the camera I’d set up ahead of time, expose the plate, and scoot on back to process it. I had an open time of about 15 minutes, so I could set up the camera within quite a range around my car. The advantage of working in wet plate over dry plate was real results in real time, so if a shot hadn’t worked out how I wanted I could just keep working at it. This could go on for a few hours, and I managed to encounter all sorts of new things.

In other words I did a lot of productive failing in my first few days.

Rough and Tumble Lessons

- Temperature! Up until now I’ve played with wet plate in a studio situation. From one plate to the next, in a studio the temperature doesn’t change much. In the field in winter, if the sun goes behind a cloud you’ll notice, because your collodion starts to get stiff while you’re trying to pour it and forms a glob if you don’t move fast enough. The lower temperature also means that the collodion takes longer to ‘set’ before you put it in the silver bath, so you have to be conscious of leaving enough time with your plate just laying flat before you pop it in the dipping bath, or you’ll get the characteristic “slumping” ripples in your image. I found a minute and a half worked for me in my circumstances.

- Wind! Pouring plates outside of the dark box on the first day, I had two plates fly right out of my hand when the wind picked up suddenly. I changed my process to pour inside the box, and was much happier for it. The way you do things in the field will be constantly evolving.

- Developer! Again linked to temperature, but you’ll probably find that you need to adjust the amount of restrainer in your developer to suit your purposes. You’ll also want to be sure to bring filtering equipment to remove any particulates that settle to the bottom of your developer, or else you’ll get veiling on your image. I neglected to bring filtering equipment with me, so by the end of the week and the bottom of my bottle of developer, things were getting messy. Bring the ingredients for your developer with you, and adjust as you go to meet your needs.

- Washing and Drying! I found that if I rinsed my plates thoroughly in water for a few minutes after fixing and lay them on the back seat of my car, face up on a towel, they were good to travel for the rest of the day until they made it back to the studio to be washed properly and dried.

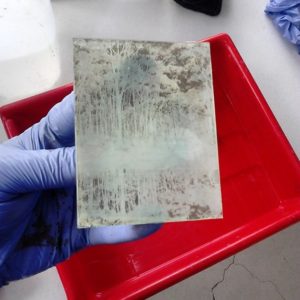

- Looking like you’re in an episode of Breaking Bad! At one point some slightly confused Police officers stopped to query what I was up to, which possibly had something to do with how I looked at the time (pictured on the left). I had a few queries from people over the course of the week, but after they saw the glass plates and I showed how they worked, they were too excited to be concerned about anything. Be friendly and try to help people understand what you’re doing – your excitement will rub off on them.

- Plates peeling! It turns out I did a rubbish job of cleaning and prepping my glass on the road. The Albumen trick saved my butt. You take some egg white and run it around the edge of the plate with a small paint brush and allow it to dry. Albumen hardens dramatically on exposure to alcohol – present in the collodion – and this coating at the edge of your plate will help your collodion stay stuck. It’s cheating, because you should make sure your plates are cleaned appropriately to begin with, but it’s a handy trick to keep up your sleeve.

- Nothing is working! I famously tell people in our wet plate workshops, “This process hates you”. Doing it in the field compounds all of the quirks that you’re used to, and adds a whole bunch more you never knew existed. For example, bees getting in your developer. That is just silly. All of these are things to learn from, and a good day failing, punctuated with a cup of tea, some books written by dead photographers, and a notepad will serve you well in getting where you want to be. Do not beat your head against the wall. The ether fumes are probably getting to you. Know when to call it quits for the day, and quit while your failure is still productive.

My time at BigCi was a wonderfully new experience, working in an entirely new set of circumstances, facing all new problems to make all new work. I’m excited to refine the parts that need refining, and expand on the bits that seem so promising. I haven’t had this much fun with my head in a box since I was 4.